You’re in a meeting. The agenda is huge. First up: a ten-million-dollar strategic pivot that will define the company’s future for the next decade. The decision is made in twelve minutes with a few polite nods.

Next item: the color of the new bike shed out back.

The meeting descends into a two-hour war. Factions are formed. Voices are raised. Detailed arguments are made about shades of green, the durability of paint, and the psychological impact of teal. Everyone has a strong, unshakeable opinion.

It’s a scene that plays out in boardrooms, non-profits, and family group chats every single day. The most trivial issues ignite the most passionate debates, while the monumental decisions slide by with barely a whisper.

This isn’t just random workplace chaos. It’s a predictable pattern of human behavior with a name. It’s called Parkinson’s Law of Triviality. And it’s the secret reason why so much of our time gets wasted on things that just don’t matter.

The Origin Story: A Nuclear Reactor and a Bicycle Shed

The law comes from Cyril Northcote Parkinson, a British naval historian and author who, in the 1950s, became a sort of cynical guru of organizational dysfunction. He wasn’t a psychologist, but he was a brilliant observer of bureaucratic absurdity.

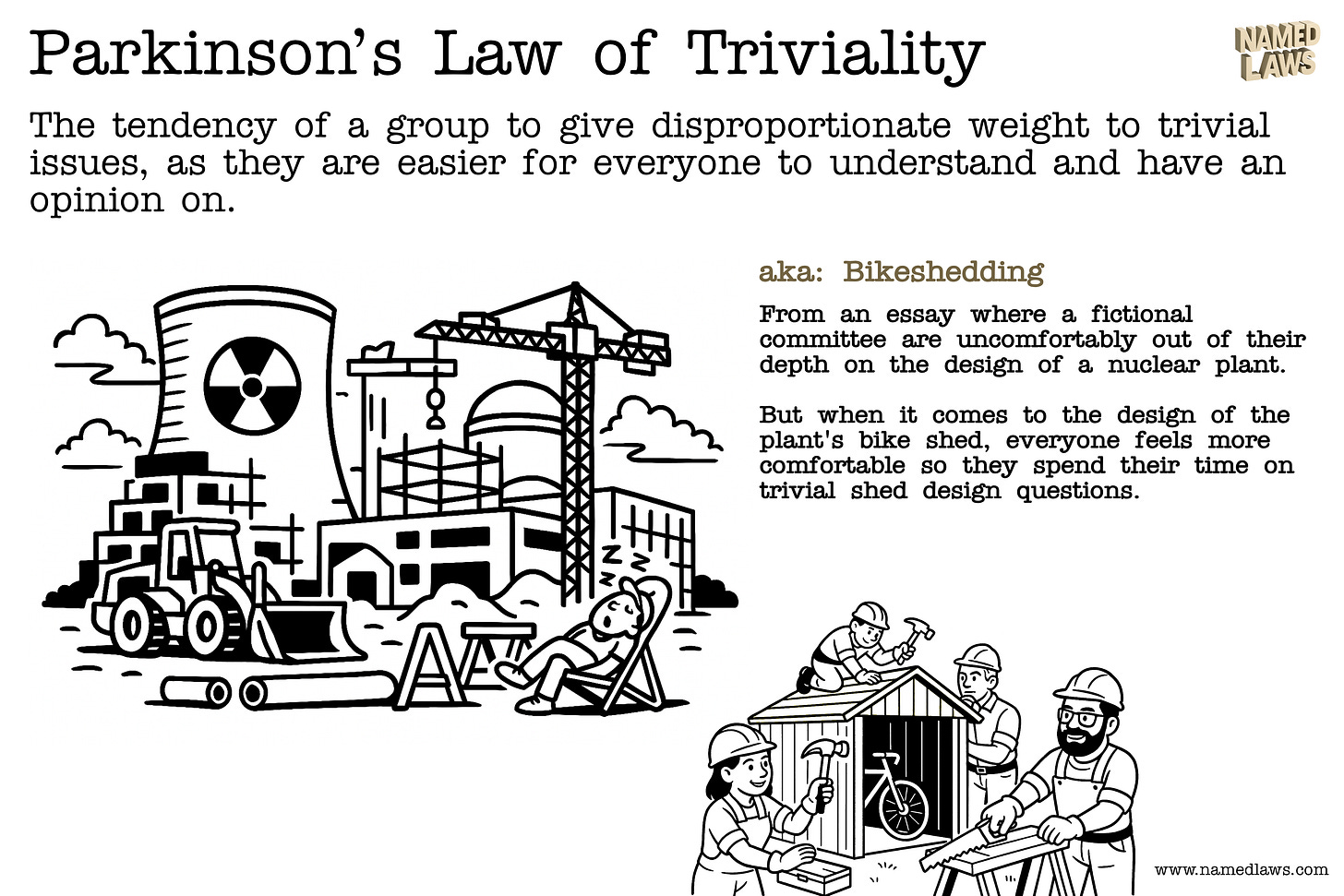

In one of his essays, he told a story about a fictional finance committee tasked with approving the plans for a nuclear power plant. The first item on the agenda is the multi-million-dollar reactor design. The details are incredibly complex, full of advanced physics and engineering concepts that are beyond the committee members. They feel intimidated and out of their depth. Unwilling to look foolish, they say very little, and the plan is approved in minutes.

Then comes the second item: a proposal for a new bicycle shed for the plant’s employees. The cost is trivial. The design is simple. And suddenly, everyone on the committee is an expert. They argue for hours. Should the roof be aluminum or asbestos? What color should it be painted? Is a bike rack really necessary?

This, Parkinson observed, is where the real “work” of the committee happens. The phenomenon became so famous that it earned a nickname: bikeshedding. It’s the act of focusing on the trivial because it’s the only thing everyone feels qualified to discuss.

The Basic Explanation

Parkinson’s Law of Triviality states that the amount of time a group spends discussing an issue is in inverse proportion to its importance and complexity. In other words, the easier it is to understand, the more people will have an opinion, and the longer the debate will last.

Why does this happen? It’s not because people are stupid. It’s because we’re human.

Everyone Wants to Contribute: In a group setting, people want to feel useful. They want to add value. When a topic is too complex, like a nuclear reactor design, most people stay quiet to avoid looking ignorant. But a bike shed? Everyone’s seen a bike shed. Everyone has an opinion. It’s an easy way to demonstrate engagement and feel like you’re contributing.

It’s Intellectually Safe: Arguing about the company’s five-year financial strategy is risky. If you’re wrong, you look incompetent. Arguing about the brand of coffee in the breakroom? The stakes are zero. It’s a low-risk way to have a strong opinion and exercise a little bit of power.

The Illusion of Progress: Debating a trivial issue feels productive. You’re making decisions! You’re reaching a consensus! It gives the group a satisfying sense of accomplishment, even if the actual accomplishment is meaningless. It’s a form of productive procrastination.

Bikeshedding in the Wild

Once you know what to look for, you’ll see bikeshedding everywhere. It’s the hidden engine of inefficient meetings and pointless arguments.

The Software Team: A team of brilliant engineers will spend an hour arguing about using snake case vs. camel case for variables in the code but will approve a major architectural change with almost no discussion. Why? Because everyone can have an opinion on a name. Only a few can debate the merits of a microservices architecture.

The Wedding Planners: A couple will agree on a $50,000 venue and catering budget in an afternoon. They will then spend the next three weeks locked in a bitter cold war over the font on the wedding invitations.

The Marketing Department: The team will sign off on a million-dollar media buy in fifteen minutes. They will then spend the next two hours in a heated debate over the exact wording of a single tweet.

How to Stop Building Bike Sheds

Parkinson’s Law of Triviality isn’t just a funny observation; it’s a diagnosis. And once you have a diagnosis, you can find a cure. Here’s how to stop from endlessly debating the bike shed.

Step 1: Put a Price on Time.

Before a discussion begins, have someone (usually the leader) frame the decision in terms of its actual business impact. “Okay, team, this is a $500 decision, let’s give it five minutes.” This simple framing helps put the issue in perspective and prevents a minor topic from hijacking the agenda.

Step 2: Delegate the Trivial.

Not every decision needs a committee. For low-stakes issues, empower one person to make the final call. “Sarah, you’re in charge of the new coffee machine. Pick one and let us know what you decide.” This frees up the group’s collective brainpower for the things that actually matter.

Step 3: Tackle the Big Rocks First.

Structure your meetings to address the most complex and important topics at the beginning, when everyone’s energy and focus are at their peak. Leave the trivial stuff for the last ten minutes, if you get to it at all.

Step 4: Gently Call It Out.

When you see a discussion spiraling into the trivial, you can be the one to gently pull it back. A simple, “This is a great discussion, but I’m conscious of the time. I think we might be bikeshedding a bit. Can we move on to the budget?” can work wonders.

The Bottom Line

Parkinson’s Law of Triviality is a reminder that groups, left to their own devices, will naturally gravitate toward the easy and the comfortable. We’d all rather have a confident opinion on a bike shed than a confused one on a nuclear reactor.

But the most effective teams are the ones who learn to resist this pull. They have the discipline to focus their energy on the complex, important problems, even when it’s uncomfortable.

So the next time you find yourself in a two-hour debate about something that doesn’t matter, remember the bike shed. And be the person who has the courage to point everyone back toward the reactor.

Named Law: Parkinson’s Law of Triviality (Bikeshedding)

Simple Definition: The tendency of a group to give disproportionate weight to trivial issues, as they are easier for everyone to understand and have an opinion on.

Origin: Coined by C. Northcote Parkinson in the 1950s, illustrated by a committee that ignores a nuclear reactor design to debate a bike shed.

Wikipedia: Law of Triviality

Category: Human Behavior & Psychology

Subcategory: Productivity & Motivation