You’re scrolling through your news feed, and there it is. A headline, dripping with intrigue, that stops your thumb mid-flick.

“Is Your Morning Coffee Secretly Killing You?”

A jolt of panic. You love your coffee. You need your coffee. You click, your heart pounding, and wade through ten paragraphs of vague studies and expert-quotes-without-context, only to arrive at the final sentence: “While more research is needed, current evidence does not suggest a direct link.”

So... the answer is no.

You’ve just been played. You fell for one of the established tricks from the digital media playbook, a lazy form of journalism so common that it has its own name. A simple, cynical, and incredibly useful rule for navigating the modern world.

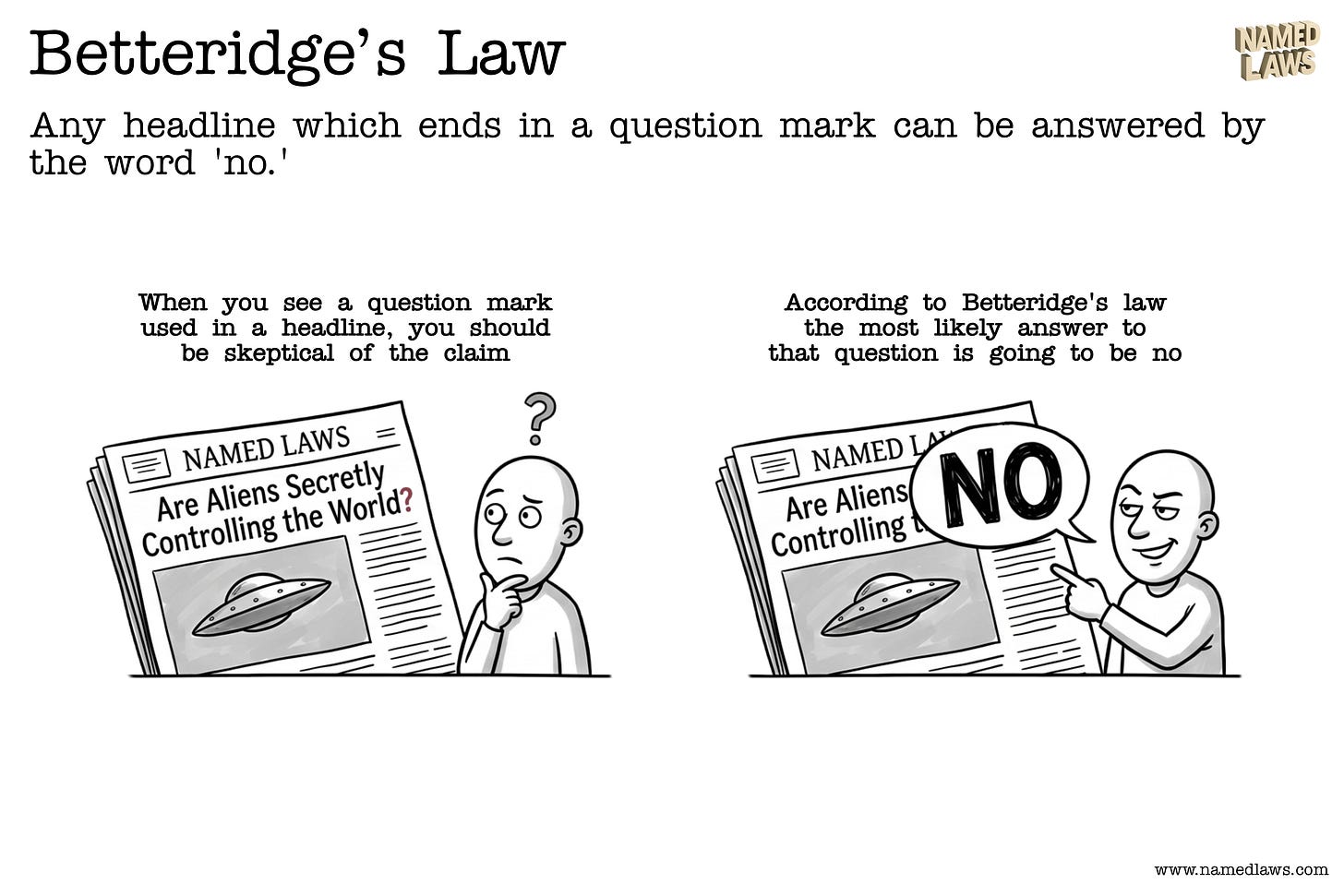

It’s called Betteridge’s Law of Headlines.

The Origin Story

The law comes from Ian Betteridge, a British technology journalist who, back in 2009, got fed up with a particular flavor of bad reporting. He saw an article on the tech blog TechCrunch with a headline that asked a provocative question about whether the music service Last.fm was sharing user data with the recording industry (the RIAA).

The article caused a stir, but the actual answer, buried in the text, was a simple “no.” The damage, however, was done. The mere suggestion was enough to create suspicion. Betteridge, frustrated by this journalistic sleight of hand, laid out a simple principle in a blog post:

“Any headline which ends in a question mark can be answered by the word ‘no.’”

He argued that if a publication had the facts to back up a sensational claim, they would state it as a fact. The question mark is a get-out-of-jail-free card, a way for a writer to float a juicy rumor without being held accountable for its truth. It was a diagnosis of irresponsible, speculative journalism, and it became an instant classic.

The Basic Explanation

Betteridge’s Law is a simple heuristic for media literacy. It’s a mental shortcut that says a question in a headline is a giant red flag. The logic is brutally simple:

If a writer has proof, they make a statement. If they don’t have proof, they ask a question.

Think of it like gossip:

The Statement: “John is quitting.” This is a factual claim. The person saying it is confident in their information.

The Question: “Is John quitting?” This is speculation. The person doesn’t know for sure, but the question itself is juicy enough to spread. It creates drama without the risk of being proven wrong.

A question headline is a form of journalistic hedging. It allows a publication to get all the clicks and engagement from a sensational idea (”Is Christopher Walken an alien?”) without the pesky burden of, you know, proving it. The answer is almost always “no,” but by the time you figure that out, they already have your click.

Betteridge’s Law in the Wild

Once you have a name for it, you see this law as the engine behind a huge chunk of the internet’s most annoying content.

Health & Wellness Clickbait: “Does This One Weird Fruit Cure Cancer?” (No.) “Is Your Tap Water Making You Stupid?” (No.) “Will This Diet Help You Lose 10 Pounds in a Day?” (Definitely no.)

Tech Hype and Fearmongering: “Is This New App Spying on You?” (Probably not in the way the headline implies.) “Will AI Take All Our Jobs by Next Year?” (No.)

Political Speculation: “Is the President Considering a Radical New Policy?” (If they were, a real journalist would have a source confirming it.)

Celebrity Gossip: “Are These Two Stars Secretly Dating?” (If there were photos, the headline would be “They’re Dating!”)

The law is the ultimate clickbait detector. It’s the “check engine” light for a news story.

How to Use This Law as a Mental Model

This law isn’t just a cynical observation; it’s a practical tool for saving your time and your sanity in an information-saturated world.

Step 1: Spot the Question Mark.

When you see a headline ending in a question, your internal “no” alarm should go off. This is the first and most important step.

Step 2: Mentally Answer “No” and Move On.

For most sensational headlines, you can just assume the answer is “no” and save yourself the click. You’ve just used Betteridge’s Law to filter out low-quality information in less than a second.

Step 3: Consider the Source.

Is the headline from a reputable news organization known for its rigorous fact-checking, or is it from a content farm designed to generate ad revenue? The law is most powerful when applied to the latter. Reputable sources sometimes use questions to frame genuine, open-ended inquiries, but even then, be skeptical.

Step 4: Demand Better.

The more we ignore clickbait questions, the less incentive publications have to write them. By refusing to take the bait, you’re casting a small vote for a media landscape that values facts over questions.

The Bottom Line

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines is a simple, powerful, and slightly depressing truth about modern media. It’s a reminder that in the fierce competition for our attention, a provocative question is often more profitable than a straight answer.

It’s not a perfect, unbreakable rule, but it’s one of the best mental filters you can have. It encourages critical thinking, saves you from countless rabbit holes of misinformation, and helps you spot the difference between a story and a non-story.

So the next time you see a headline that asks a wild, speculative question, just remember the law. The answer is probably “no.” And your time is probably better spent reading something else.

Named Law: Betteridge’s Law of Headlines

Simple Definition: Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word “no”.

Origin: Formulated by British technology journalist Ian Betteridge in 2009.

More Info: Grokipedia, Wikipedia

Category: Human Behavior & Psychology

Subcategory: Communication & Rhetoric